Once upon a time, this was all forest. Or almost.

When the Celts arrived in the 6th century BC and named the area Medhelan, they found a landscape made up of woodlands—mainly oak, turkey oak, hornbeam, elm, hazel, willow, alder and poplar—mixed with springs, marshes and small clearings cultivated by pre-Celtic communities. Centuries later, when the Romans arrived and the village of Medhelan gradually became the city of Mediolanum, the situation had not yet drastically changed: the land was increasingly shaped for urban and agricultural purposes and became less wild, but it was still dominated by forests and wetlands.

Even in The Charterhouse of Parma, set during the Napoleonic era, Stendhal speaks of the forests surrounding Milan that remained wooded until the Industrial Revolution. It was then, starting from the north, that factories began gradually occupying more and more land, while the southern area remained—and in part still is—more agricultural, as we can see with the Parco Agricolo Sud (in English, Southern Agricultural Park).

This North–South divide is far from coincidental. It is in fact rooted in the nature of the terrain: the upper Po Valley in the north is gravelly, causing water to seep deep underground and making the soil less suitable for agriculture. In contrast, the southern area has clay-rich soil, which brings water closer to the surface through natural springs. This led to the development—starting around the 12th century—of the marcite technique, a method of irrigated grass cultivation that played a fundamental role in shaping the agricultural landscape around Milan.

La Certosa di Parma di Stendhal

Milan and its wild and semi-wild green spaces

So what remains today of the woods and forests that, in times not so distant — such as in Stendhal’s era — once characterised Milan? Unsurprisingly, very little. As former Forestry Corps commander Alberto Guzzi writes in the preface to Milano Selvatica by Stefano Fusi, "Milan has green areas that are significant, not many, but still important. These include historic and monumental sites such as the gardens of Via Palestro and Villa Reale, Parco Sempione, and Parco Lambro (as a result of the pre-World War II urban planning of the city). Milan also has large tree-lined avenues and ring roads. In short, there is a certain amount of managed urban greenery. What is missing—and only recently being recognised—is the presence of spontaneous greenery, of the wild, of the natural."

In his essay Milano Selvatica — a thoughtful, passionate and at times poetic map — journalist and environmentalist Stefano Fusi explores what remains, what is under threat, and what is coming back of Milan’s wild side. In a nutshell, Milan’s major green areas can be grouped into three main categories: the classic Italian-style parks (such as Parco Sempione or the Giardini di Porta Venezia), the semi-wild parks (like Parco Nord or Boscoincittà), and finally, the rarest of all — spontaneous forests, as mentioned earlier.

Milano Selvatica di Stefano Fusi, una mappa del verde selvatico a Milano, di quel che ne resta e possiamo ancora salvare

Parco Nord is certainly an excellent example of a semi-wild area," Stefano Fusi explains to me. "It’s neither too much of a park nor too little of a forest. In part, it followed the same model developed just a few years earlier for Boscoincittà. Both were inaugurated in the 1970s, a time when there was an open debate about what to do with these peripheral zones—former agricultural lands like Boscoincittà or former industrial sites like Parco Nord, once home to the Breda Aeronautica plant.

In that case, a good job was done: to this day, part of the forest has been preserved. For example, fallen trees aren’t removed, and the park’s managed with a naturalistic approach. Other parts of Parco Nord are more like a traditional park. But there’s a balance: it’s a kind of puzzle, but a well-built one.”

While these semi-wild parks are the result of planning, political will and civic involvement—Fusi himself helped establish Boscoincittà by physically planting and watering trees—the case of spontaneous urban forests, as the name suggests, is different. The most well-known example is Piazza d’Armi: a vast area of around 42 hectares in Milan’s western Baggio district, which until the late 19th century was agricultural land dotted with farmhouses and irrigation canals. It was later converted into a military training ground and used for exercises until the 1980s, when it was gradually abandoned. Since then, without any direct human intervention, nature has slowly reclaimed space.

In just a few decades, Piazza d’Armi has become a rare example of a spontaneous urban forest, home to trees, shrubs and untamed meadows that support a rich biodiversity: birds of prey, amphibians, small mammals and insects. “The presence of animals isn’t just something romantic,” Fusi says. “In fact, they’re some important ecological indicators—when species like squirrels or owls show up, it means the environment is quite rich and diverse.”

The transformation of Piazza d’Armi was spontaneous and unplanned, but today it risks being altered for real estate development. Several local groups, such as Le Giardiniere (The Gardeners, in English), are proposing an alternative way: to preserve the forest while integrating it with urban gardens, educational trails and small-scale agricultural initiatives.

A model not too different from the one conceived for the woodland section of the Goccia (you can explore the Goccia’s story by browsing this site or reading more here).

Oriented nature reserves

“In all these abandoned areas, nature grows spontaneously,” Fusi explains. “And it’s important that they’re protected not as traditional urban parks, because the context is clearly different. We should treat them as “oriented nature reserves”: areas that can be visited, where scientific research can take place, and which the public can enjoy, but in a controlled way and under the guidance of dedicated organisations. In short, not a classic park where you stroll in with your dog or bike, because that would be incompatible with the conservation efforts.”

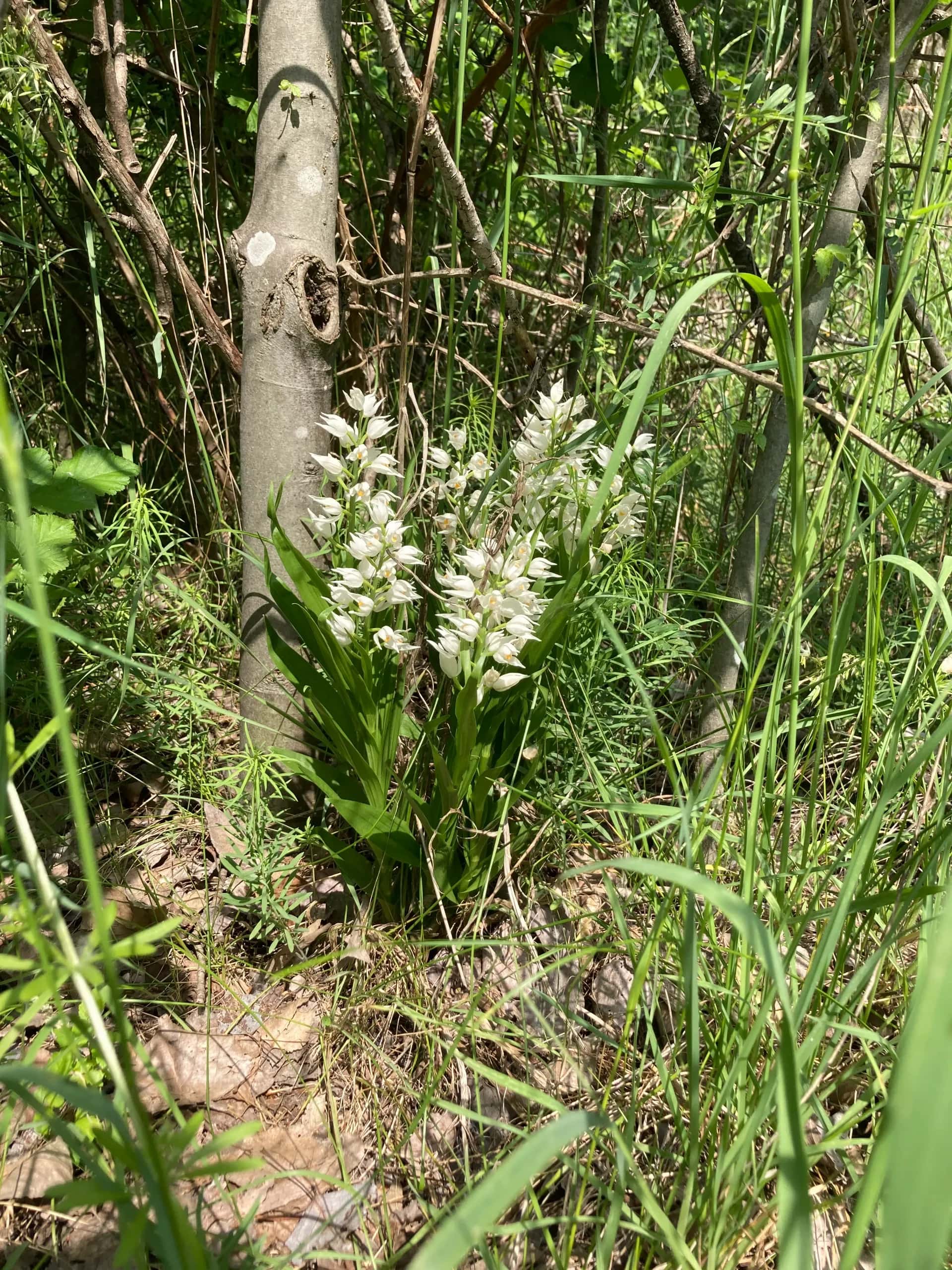

The Goccia Forest, where around 250 plant species have been recorded and numerous animals have found shelter — including foxes (arrived from the north following the railway), tawny owls, buzzards, hedgehogs, woodpeckers, grass snakes and owls— is one of the very few examples of a spontaneous urban forest in Milan.

In addition to the Goccia and the aforementioned Piazza d’Armi, other examples include the small woodland at the former Crescenzago cemetery and the Rogoredo forest. Or perhaps it would be more accurate to say the latter ‘used to be’ an example, as Fusi explains: “It has basically been turned into a regular park, also as a way to counter drug dealing. Many trees were cut down, too many. There’s now a mountain bike trail and the area sees much more footfall than before, when no one dared enter due to its reputation. On the one hand, this is a positive shift; on the other, we must be careful to protect certain parts like the ponds that formed spontaneously, where swans and other birds, even rare ones never seen in the area before, have begun to appear. It’s even become a destination for birdwatchers.”

Cephalanthera-longifolia, una delle 250 specie botaniche diffuse nella Foresta della Goccia. @Terrapreta

Wild greenery and heat

One of the reasons why it is crucial to protect—and, if anything, expand—wooded and semi-wooded areas has become especially clear during this summer of 2025, as Milan’s temperatures began exceeding 35°C as early as mid-June. “Wild areas help mitigate urban heat islands, regulate the local climate, purify the air, and provide refuge for biodiversity, including vital pollinators. Like other major cities, Milan is becoming a furnace in the summer. But the moment you step into the Goccia, you immediately feel the difference.” Fusi says

In an area like Bovisa, where green space is virtually absent, the cooling relief you can feel when entering the Goccia forest becomes even more noticeable as you venture deeper inside—offering a clear confirmation of Fusi’s words: “All this means wellbeing and health. It means giving residents the chance to enjoy these places, to have somewhere to walk. And it all comes at zero cost, since nature does it all on its own, spontaneously. It also helps reduce pressure on the national health system, for example by lowering stress levels.”

And yet, as an ISTAT survey confirmed in 2020 [Note of the Translator: the Istituto Nazionale di Statistica (ISTAT) is Italy’s national public research body responsible for producing official statistics], Milan has very little green space: the total percentage hovers around 13%, while Rome and Naples are both above 30%. Milan’s green coverage is among the lowest in Italy and in Europe.

“Considering that we’re also one of the most polluted cities—partly because we’re in a basin like the Po Valley—it should be the bare minimum to protect these areas,” Fusi notes. “Instead, there’s very little attention. In fact, we could even say there’s open hostility, since these spaces are often seen as sites for development and are therefore under constant threat.”

It’s partly a cultural legacy, one that dates back to the decades when people fled the countryside for the city in search of better living conditions, viewing nature as something to escape or shut out, Fusi explains: “We’re still stuck in that mindset, even unconsciously at times. People think they love nature, but often they don’t really understand what that means. They see a fallen tree in a park and think it’s a sign of disorder, something to be removed. We have the tradition of the Italian garden, where everything is geometric and tidy:it reflects a certain cultural model. And yet, we could be the country with the greatest biodiversity in the world.”

The Rinnovata Pizzigoni School

So, how can we spread a different vision? And how can we protect what remains of the wild in Milan? There are associations and local committees. Certain political parties or administrations show more sensitivity to the issue. But education, starting from the very first years of school, has an essential role to play. A few hundred metres from the Goccia forest, just beyond the tracks of Villapizzone station, down a small street off Via Mac Mahon, there is a primary school founded in 1927 by Giuseppina Pizzigoni. It’s the Rinnovata Pizzigoni: the school Stefano Fusi attended as a child—and that, a few decades later, I attended too.

It’s a school unlike most others, where children have the chance to spend plenty of time outdoors among animals (I personally remember donkeys, chickens and turtles), tending to small vegetable gardens, and working in greenhouses. In short, where traditional lessons are alternated with a more nature-oriented approach. “La Rinnovata was a pioneer, a real example,” says Fusi. “Nowadays, lots of schools have gardens—it’s become a trend, thankfully. But the Pizzigoni method has remained confined to the Rinnovata: no one really followed her lead. Some things were almost science fiction at that time like the fact that classrooms opened directly onto the garden, creating a direct link with the outdoors, with nature, with the trees. It was a completely different model from what you might call the ‘military-style’ school layout, which was dominant then and, in part, still is today.”

The value and legacy of the Rinnovata Pizzigoni became clear to Stefano Fusi much later, when in the 1970s he helped create Boscoincittà: “As a child, I had the chance to understand what a garden was, to work with my hands in the soil. Later, when I was involved in the creation of Boscoincittà, I saw children from traditional primary schools come to help with planting trees, watering. But they didn’t know how any of it worked: some of them wanted to plant the saplings with the roots facing up and the branches in the ground. And that’s when I truly realised what it meant to have attended the Rinnovata and to have learned the things I did.”

The awareness-raising work of the Rinnovata and the growing attention to these issues within education become crucial when it comes to valuing green spaces and being able to recognise greenwashing. These are the kinds of operations where, for example, a small park like the Biblioteca degli Alberi, with its struggling saplings and manicured lawns, is promoted as a valid alternative to the spontaneous woodland of Melchiorre Gioia, which existed in the same area of Milan until just a few years ago—before being cleared to make way for the new regional government skyscraper.

The oases

A more useful model—one that has been gaining traction in recent years—is that of the “oasis”, found mostly in the outer ring of the metropolitan area or in the Brianza region. What defines these areas is first and foremost the presence of water (streams, rivers, ponds, etc.) and the presence of wildlife, including dormice, badgers, toads and, in some cases, even roe deer.

“The best-known oasis is the one in Vanzago, one of the first built by the WWF,” Fusi says. “But it’s already a bit far from Milan, located Northwest between Rho and Arluno. Then there’s the Levadina oasis near Linate, the Smeraldino oasis in Rozzano, and the Caloggio oasis in Bollate, where there used to be, and still are, spring-fed pools. A stream called the Nirone runs through it, and there’s a beautiful small woodland, part of which is off-limits for conservation reasons.”

The way these oases are managed—ranging in size from just a few dozen to over 200 hectares—is quite different from that of parks or similar spaces. Their primary aim is to protect biodiversity, create ecological corridors, and provide refuge for wildlife. They are open to visitors, but access is limited and must be respectful. These are also places frequently visited for research and educational purposes.

This is the same approach that will be followed for the Goccia Forest: not a traditional park for dog walking or cycling, but a network of paths designed to let visitors experience the surrounding nature while respecting its balance. The goal is to allow those 18 hectares spared from concrete—the majority of the forest—to continue growing spontaneously.

Andrea Daniele Signorelli. is a freelance journalist specialising in the relationship between new technologies, politics and society. He writes for Domani, Wired, Repubblica, Il Tascabile and other outlets. He is the author of the podcast “Crash – La chiave per il digitale”. His latest essay is “Simulacri digitali: le allucinazioni e gli inganni delle nuove tecnologie” (Digital Simulacra: The Hallucinations and Deceptions of New Technologies).