Michael Marder is best known for his research on the philosophy of plants and the concept of “plant-thinking”. In his works, he explores how plants can offer a new perspective on subjectivity, temporality and knowledge, challenging traditional anthropocentric philosophical categories. According to Marder, “plant thinking” is a non-cognitive, non-ideational and non-imaginative mode of thinking, the understanding of which could transform human thinking, leading it to borrow the qualities and capacities of plants to relate, communicate and interact with the environment and other beings.

He is a philosopher and currently teaches at the University of the Basque Country. His work focuses primarily on continental philosophy, environmental thought and political philosophy. He received his PhD in philosophy from the New School for Social Research in New York City and conducted postdoctoral research at the University of Toronto. He also taught at several universities, including Georgetown University and Duquesne University, before accepting the Ikerbasque professorship.

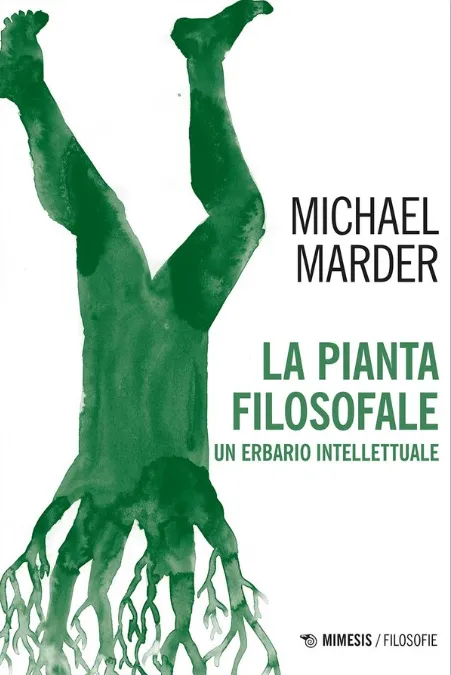

He is the author of several books and essays that have been translated worldwide. In Italy, he has published with Mimesis: Time Unknown: A Philosophical Glossary for the Twenty-First Century (with G. Tusa, 2024), Chernobyl Herbarium: Life After the Nuclear Disaster (2021), and The Philosopher's Plant: An Intellectual Herbarium (2025).

In The Philosopher's Plant: An Intellectual Herbarium, published in Italy by Mimesis, Michael Marder explores the profound and often overlooked relationship between philosophy and the plant world.

Western philosophy has traditionally shown a conceptual disinterest, if not outright aversion, towards plants. Always relegated to an inferior role compared to animals and humans, they have been considered devoid of consciousness, intelligence or autonomous movement, and used only as metaphors or scenic backdrops. According to Marder, however, plants have still found ways to influence philosophical thought.

@edizioni Mimesis

Through twelve chapters, each dedicated to a significant philosopher (from Plato to Irigaray) and a specific plant, Marder illustrates how these plants have influenced metaphors, concepts and philosophical arguments, suggesting that plants can offer important lessons on the relationship with otherness, temporality, knowledge and the nature of being, promoting a non-anthropocentric perspective.

The idea emerging is that the instrumentalisation of plants, and considering them ontologically inferior, is part of an “overly human” and “totalising” logic that has had negative consequences for our relationship with the so-called natural world.

The Philosopher's Plant is not only a reinterpretation of the history of philosophy through plants, but also an invitation to rethink philosophy itself from a plant perspective, questioning the principles that our society has established regarding life, thought, and the place of human beings in the world. These reflections are in line with the concept that Michael Marder develops in one of his early books, “plant-thinking”. It is not a question of attributing to plants a consciousness or intelligence similar to that of humans, but rather of recognising their unique form of existence and their capacity for interaction with the world, which is totally different from that of humans. For Marder, this is a non-cognitive mode of thinking: this “headless thinking” manifests itself in their growth, their responses to the environment and their capacity for interconnection. It is a form of non-conscious intentionality.

Starting from the apparent difference between the plant world and human beings, is it possible that plants can act as a mirror of us? And how? Is it possible for 21st-century human beings to understand themselves through plant life and its history?

The question of whether plants can mirror us humans presupposes a certain metaphysical division that has long been the basis of Western thought: that between the human and the non-human, the animate and the inanimate, the thinking subject and the vegetative body (after all, mirroring requires distance and separation, placing something or someone in front of the mirror, or above and against it). Within this framework, plants have always been placed on the passive, silent, immobile side: something that forms the backdrop to human life, but never as a participant in the drama of meaning, thought or reflection. If we want to address the question of plant mirroring with any philosophical seriousness, we must first of all pause to dismantle the conceptual framework that maintains the formal otherness between us and plant life, discovering the plant as the other within the human.

Plants do not reflect us in the narcissistic way of a reflective surface, which returns our image, our categories, our values. They do not offer a recognisable imitation of human form or psyche; on the contrary, they oppose this reduction to what we can already understand. Yet there is a mirror, if we are willing to rethink the very notion of a mirror. What the plant offers is not a mirror of sameness, but a mirror of difference, of otherness, a vegetal counter-image that forces us to confront the narrowness of our anthropocentric horizon.

The plant, in its rootedness, in its radical passivity that is also an active engagement with the world through photosynthesis, tropisms and exquisite attention to its environment, offers a way of being that does not conform to human ideals of autonomy, will or even time. In encountering this type of life, we are confronted with our own prejudices. The plant does not reflect what we are, but rather exposes what we are not yet able to think of ourselves and, in the same way, what we are no longer able to think of ourselves, having completely forgotten and repressed it.

Thus, plants can indeed reflect us, but only by distorting our image, making it strange, opaque and unfamiliar. It is in this estrangement that the possibility of transformation lies. Understanding ourselves through the life of plants does not simply mean grafting plant metaphors onto human psychology or history, but rather opening ourselves up to plant thinking. A way of thinking that does not separate the subject from the object, the mind from the body, or the self from the world. In this way of thinking, we do not separate ourselves from the plant, looking down on it from a throne of reason; we think with and through plant life, allowing its temporalities, sensibilities and relationships to guide us towards a different ethos. In short, I would say that the plant is our forgotten relative, our silent interlocutor and perhaps the very soil from which a new understanding of humanity can spring.

-1920x1080.webp&w=3840&q=60)

©Camilla Morino

Related to the idea of plants as mirrors is the possibility of understanding and experiencing them as silent (but sometimes very explicit) witnesses to our lives and our history, from the most private and domestic sphere to the most general and epochal. What testimony do plants bear?

The testimony of plants is not like that of historians or archivists in the human sense, but occurs in a deeper and more elemental way, as it is inscribed in their bodies, their rhythms, their resilience and their continuous metamorphoses. To ask what the testimony of plants is means listening to a voice that speaks of growth, decay, response to trauma and healing.

Plant testimony is participatory, rooted in places of life and loss, and inhabits our most intimate spaces—our gardens, our homes, our rituals—as well as the public landscapes of violence, colonisation, industrialisation, and environmental degradation. Trees growing on land bearing the marks of war (including the corpses of fallen soldiers and, increasingly, the ecocide wrought by invading armies); crops altered by climate change; houseplants subject to care or neglect: these are all plant inscriptions, embodied records of human-plant histories, told and untold.

Plants bear witness not only to events, but also to atmospheres – to the subtle, invisible and pervasive conditions of existence. They record toxicity; they bend towards or away from our presence; they express without words drought and depleted soils, nitrogen-filled air and radioactive isotopes. Their testimony is distributed, diffuse, ecological. It resists the linearity of chronicle or confession. In this way, it accumulates slowly and often irreversibly.

For plants, bearing witness means persisting, remaining and transforming in the wake of disruption. It also means making visible, through their altered forms and interrupted life cycles, the invisible operations of power, abandonment and care. They are witnesses not to the spectacular, but to the habitual, the neglected, the effects sedimented over time.

In this sense, plants not only bear witness to our history, but complicate it. They reflect back to us (and here we return to the strange mirror of your first question) not what we already know, but what we have refused to see: the slow violence of ecological collapse, the forgotten kinship between species, the ethical demands of coexistence.

%2520(1)-1920x1080.webp&w=3840&q=60)

©Camilla Morino

If plant thinking is non-cognitive, what kind of knowledge does the plant world possess? What do they know that we do not? How can they teach us? And how can we learn it?

When I write that plant thinking is non-cognitive, I am not denying that plants think. Rather, I want to free their thinking from the monopoly of cognitivism on what it means to think, linked exclusively to rationality, symbolisation and interiority. What the plant world offers is pre-reflective, embodied and dispersed thinking, an intelligence that unfolds in growth, sensitivity to the environment and symbiosis. Plant knowledge is not knowledge of the world, but knowledge as a relationship with the world.

This type of knowledge needs neither language nor abstract concepts. It is intimate, ecological and reactive, singular and highly transmissible. Without realising it, our common conception of knowledge is also based on this, even if we do not recognise this “foundation”. Plants know how to inhabit very different worlds at the same time. They know how to wait, endure, cooperate in a non-hierarchical way, and regenerate after a catastrophe without conquest or revenge. They embody a type of wisdom that escapes anthropocentric criteria of utility and clarity. Their knowledge is expressed in rhythms, orientations, and relationships, rather than in representations.

What do they know that we do not? They know the art of being-with: of synergistic coexistence with the soil, the sun, the air, and others. Furthermore, they know how to respond without dominating, how to give without expecting anything in return, how to die and be reborn without the drama of existential rupture.

Plants can teach us, but only if we first unlearn the arrogance of what usually goes by the name of epistemology. Their lessons come in the form of constantly changing gestures and positions: the slow curling of a tendril and the opening of a leaf or flower towards the light, the communal signalling of forest root systems, the refusal to be caught up in haste or to separate oneself from places. Plant thinking, in fact, invites us to another way of being, in which thought is not separate from life and knowledge is not separate from the world it seeks to know.

-1920x1080.webp&w=3840&q=60)

©Camilla Morino

After reading it, the impression is that the Philosopher's Plant is nothing more than reflection itself, the history of Western philosophy told by a philosopher through anecdotes about the relationship between plants and philosophers. Yet, at the same time, it is much more than that because, as a concept and symbol of the relationship between human beings and the plant world, it transcends the boundaries of species, kingdom and domain. What words can we use to describe it?

Defining The Philosopher's Plant as a reflection on Western philosophy through anecdotes involving thinkers and plants is, in a sense, accurate, but only as a starting point. My project goes beyond symbolic gesture to the extent that it aims to reconfigure what it means to think, narrate and relate. The form I have employed—and which I invented to capture this condition—is that of the phyto-biography, which I then extended to the phyto-auto-hetero-biography, particularly in my 2016 books Through Vegetal Being, written with Luce Irigaray, and The Chernobyl Herbarium, created with Anais Tondeur. In short, the story of a life is not exclusively one's own (auto), nor only that of another (hetero), nor only that of plants (phyto), but a composite design that reveals how human subjectivity – especially philosophical subjectivity – is constituted through and alongside plant being. It is a writing that undermines the notion of a delimited and sovereign “I”, showing instead how thought emerges from commitment, shared exposure, rootedness in a place and time, as well as from uprooting and upheaval.

Thus, each chapter of The Philosopher's Plant becomes a sort of phytobiography: not a biography of a plant, nor simply of a philosopher, and their respective ways of thinking, but an encounter between the two, a co-articulation of existence that neither subject can fully possess. In these encounters, plants guide thought, providing it with material support and disrupting its categories. Their influence is often opaque to philosophers themselves, but it is intertwined with their concepts, metaphors, habits and gestures.

It is true that, if we want to describe such a hybrid form, we must abandon disciplinary boundaries and embrace a vegetal style of thinking and writing that, shunning the language of domination, bends like a stem or a branch growing towards the light, where meaning is photosynthetic: generated in the exposure between oneself, the other and the world. But this, in turn, implies abandoning ontological boundaries and classification systems. Thus, the philosopher's plant transcends species and regions of being, because it points to something deeper: the interdependence of all forms of life and thought.

Marco Liberatore. Marco Liberatore è un ricercatore indipendente, consulente editoriale e giornalista culturale. Si occupa di cultura digitale, ecologia della rete e tecno-politica. Co-dirige la collana Culture Radicali per l'editore Meltemi e le collane Postuman3 e Selene per Mimesis edizioni. Collabora con il quotidiano Il Manifesto e con diverse testate on-line. Con il gruppo di ricerca Ippolita ha pubblicato Hacking del sé (2024), Etica hacker e anarco-capitalismo (2019), Tecnologie del dominio (2017), Anime elettriche (2016). Per cheFare, di cui è co-fondatore, ha curato il volume Cultura in trasformazione (2015).

-1920x1080.webp&w=3840&q=60)