The restoration of an area and its transformation into a place rich in life for humans, flora and fauna is not merely an environmental policy initiative, but something much deeper, inviting the discovery of new forms of pleasure linked to coexistence and relationships. Stacy Alaimo joyfully affirms this at the end of this interview, in which she presents new ideas and concepts closely related to post-industrial spaces such as La Goccia.

Stacy Alaimo is a prominent American scholar who works alongside figures such as Donna Haraway, Keren Barad, Anna Tsing and Jane Bennett, among others, in a field of study that intertwines cultural, environmental and ecological studies with feminist, decolonial and indigenous studies. This field is known as neo-materialism or feminist neo-materialism. Her work combines environmental and social justice, placing itself in an interdisciplinary space where literature, art, philosophy and politics meet gender and science studies.

A professor of English and member of the Department of Environmental Studies at the University of Oregon, Alaimo is the author of numerous articles and essays. Her best-known book, Exposed: Environmental Politics and Pleasures in Posthuman Times, was recently translated into Italian under the title Allo scoperto. Politiche e piaceri ambientali in tempi postumani, published by Mimesis in the Postuman3 series, translated by Laura Fontanella and edited by Angela Balzano. In her most recent work, The Abyss Stares Back, she explores the ethical and aesthetic significance of encounters with creatures of the deep sea and our relationship with the non-human.

Trans-corporeality is a concept she has developed that describes bodies as permeable and interconnected with the environment: substances, affections and material agents cross bodily boundaries, dissolving the illusion of autonomy and independence when it comes to living beings, environments and systems. This thought recalls and intertwines with Donna Haraway's sympoiesis, which suggests an idea of continuous co-becoming between living beings, environments and technologies. Both perspectives shift the focus from the isolated subject to the relationships that constitute it. They therefore converge in a radically relational vision of existence, which problematises the idea of independent subjects and clear boundaries between organisms, places and the environment.

These theories imply a profound revision of ethics and epistemology: knowledge is not domination, but listening, care, and participatory attention; acting is not controlling, but responding responsibly to interdependencies. Trans-corporeality is, in a sense, the embodied condition of sympoiesis: bodies live and transform themselves through ecological, affective and material relationships. Together, these concepts invite us to shift our gaze from the isolated subject to the connections that constitute it, promoting a politics of shared vulnerability and coexistence, or, as Alaimo puts it, subversive vulnerability.

In an era marked by ecological and social crises, scholars such as Alaimo offer us the tools to think and act beyond anthropocentrism, helping us to change our perspective and develop an awareness of the profound interconnection between human and non-human bodies, in the understanding that subjectivities emerge from material and affective flows.

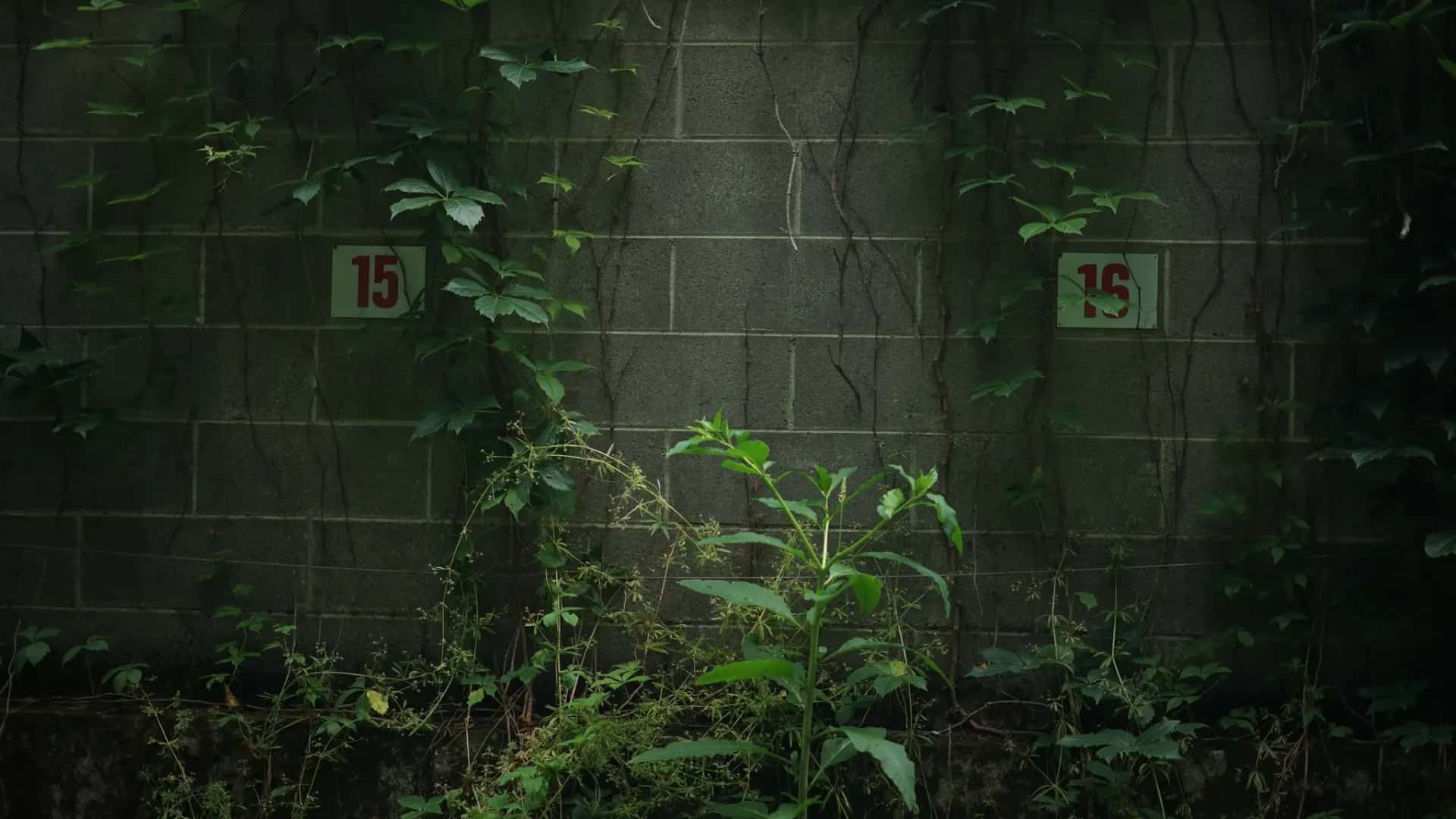

Here, Stacy Alaimo's thinking on trans-corporeal materialism helps us to develop a critical reflection on places such as Parco La Goccia, on their status as former industrial areas, and on the relationship between plants and pollutants, from an environmental perspective that does not remove the past but transforms it. The vulnerability of land awaiting remediation is both a physical and symbolic condition. These places are marked by the scars of a past that is ours, that of the city. They are wounded spaces, but also potentially fertile: their fragility makes them open to transformation. Accepting this vulnerability and coexisting with it means experimenting with a possible posthuman coexistence, where pleasure and multispecies care intertwine with the memory of industrial progress and responsibility towards these living bodies.

Your book, Allo scoperto, opens with a reference to dissolution, which is the era we are living in these years, a time characterised by violence, wars, depletion of raw materials, deadly capitalism, widespread toxicity. What does it mean to live in dissolution? What is its meaning and how is it possible, considering that, for better or worse, we are all here?

I think the best way to deal with dissolution is to accept it. Dissolution can be a radical way to experience interconnection with humans and non-humans who are harmed by capitalism and toxicity. Contemplating how the lives of shelled marine animals dissolve in acidified oceans provides a vivid sense that “the environment” is never just external to the organism, but always permeates the living being. One of the central problems for both social justice and the environment is that capitalism, like the dualisms that underpin Western culture, promotes individualism and separation. Experiencing oneself exposed to toxins, inclement weather, noise, and the stress of systemic oppression can be an invitation to take a position of subversive vulnerability, to inhabit vulnerability as political protest. Right now, in the United States, people are wearing funny and cute animal costumes to protest against the presidential regime, taking on a kind of sweetness, kindness and vulnerability to challenge fascist power. In Portland, Oregon, they organised an “emergency naked bike ride”, which is hilarious because no one *needs* a naked bike ride, yet protesting naked, as I discuss in a chapter of Allo scoperto, is a way of exposing oneself and dramatising one's immersion and vulnerability to the world.

A recurring concept is that of trans-corporeality, which seems to me to recall other concepts such as symbiogenesis, sympoiesis, inter-being, flesh of the world or body without organs. You emphasise, however, that this term indicates the material link between human beings and bodies, substances and places. You also point out that the very idea of being human is something that is never completely defined and established in a posthuman perspective. I would therefore like to ask you to explain this connection between trans-corporeality and the posthuman perspective and what kind of life practices it implies or suggests.

The concept of trans-corporeality aims to erase the framework of the Human as such, focusing on the networks between material substances and forces that pass through us and reside within each of us, influencing our bodies and minds. We act on the world and the world acts on us, through material agents that are part of the natural, post-natural, economic and political systems in which we find ourselves. Emphasising the material intertwining of human beings, rather than a delusional sense of separation and cerebral transcendence, transforms the human into the posthuman. This mode of posthumanism rejects human exceptionalism, just as it rejects the hierarchies of mind/body, human/animal, subject/object. Furthermore, trans-corporeality is posthuman in the sense that it extends to all living beings. In the Anthropocene, all living creatures dwell at the crossroads between body and place; all creatures are trans-corporeal. Place is not a passive backdrop, but is essential for food, water, shelter, and more. Just as humans may not be able to assess the toxins that consumer products, plastics, food, and water put into their bodies, animals are also unable to know whether the food or water they find is safe.

Light pollution, noise pollution, habitat destruction, climate change, and the widespread use of plastics and other chemicals affect the bodies, minds, and cultures of non-human animals, subjecting them to suffering and extinction. For me, trans-corporeality and posthumanism go hand in hand, or rather, paw in paw.

An important part of your research work deals with the agency of the sea, with the depths of the sea and life in the abyss. Contrary to what common sense might suggest, what happens down there concerns us closely. In fact, we could say that our bodies reach that far down – and so does our waste – with effects that are not always beneficial. What connects us to those environments today, in this era of dissolution, and why is it so important to observe and understand those depths?

Ocean ecosystems and habitats are interconnected, so what happens in the depths affects the ocean in a much broader way. Scientists point out that more than half of the oxygen we breathe comes from the ocean, so if ocean ecologies collapsed, it would be catastrophic. I think two very different things connect industrialised populations to the deep sea. The first is, as you say, that waste, including plastic, chemical and radioactive waste, sinks to the bottom of the seas, causing damage for hundreds of years. In addition, carbon dioxide produced by fossil fuels is not only warming the ocean, but also changing its alkalinity, which is predicted to cause widespread damage to many marine species and ecosystems. Finally, industrial-scale fishing and mining, particularly deep-sea mining, which may begin very soon, are severely damaging marine life and will continue to do so. So industrialised populations that have profited from the long history of colonialism and capitalism have a responsibility to oppose the destruction of the oceans, especially since many indigenous populations and other vulnerable groups depend on the ocean for their survival. But it is easy not to care about the ecosystems and creatures that inhabit the immense expanses and depths of the ocean. They seem too vast and distant to us. My new book, The Abyss Stares Back: Encounters with Deep Sea Life, raises the question of what might motivate people to care about creatures living on the sea floor. I think one of the most seductive and powerful incentives for extending environmental concern to the deep sea is the highly aesthetic photos and videos of life in the deep sea, which are extraordinarily beautiful and wonderfully strange. They arouse a curiosity and pleasure, even an attachment, that can motivate interest in the life of the deep.

Also in Allo scoperto, you devote several pages of the conclusion to a scathing critique of sustainability, highlighting its limitations, inconsistencies and collusions. Several years have passed since you wrote those pages. Has your opinion changed today? In particular, I would like to ask you how post-humanist epistemologies, ethics, politics and aesthetics can be cultivated. It all revolves around a change of perspective: removing not only human beings from centre stage, but also every other predefined object. And placing relationships, connections and links between beings, environments and things at the centre of observation. Is that right?

Hmmm. That's an interesting question. I still believe that top-down sustainability management systems, which treat the environment as an inert “resource” that passively awaits human use, are a model that replicates the causes underlying environmental destruction, namely the anthropocentric view that “nature” – or the whole world – exists to serve human beings. On the other hand, in the United States, the sustainability movement seems to have disappeared, and very little is being done to reduce toxic substances, plastic, or energy consumption. I think companies, institutions, schools, cities, and states need to develop systems that minimise their negative environmental impact while also implementing positive projects such as planting trees and creating natural habitats such as gardens or vegetable patches whenever possible, for example.

Yes, the relationships and connections between people, non-human life and environments should be the focus of attention, motivating us to reflect, in every area of our lives, on how our ordinary actions, practices and ways of being and knowing affect other people and other non-human lives. With the acceleration of species extinction, everything we do is important. I often think about the reasons that drive Rosi Braidotti to practise a more posthuman mode of “sustainability”, as she herself states, “for the sake of it and for the love of the world”. On a personal level, I would say that replacing my lawn with native plants and creating a habitat for insects and birds has been a beautiful, immensely joyful practice that affirms and values life. These direct actions on behalf of other beings not only help them, but also provide those who perform them with a powerful antidote to despair. Doing something positive and tangible remedies the anger and sadness we feel about all the violence we cannot control. To cultivate post-human ways of being, we must reaffirm the pleasure, beauty, joy and satisfaction that come from caring for other creatures. How fabulous it would be, for example, to reclaim an industrial area and transform it into a place full of life where people, trees, plants, birds, insects and other beings can enjoy themselves together!

Marco Liberatore. Marco Liberatore è un ricercatore indipendente, consulente editoriale e giornalista culturale. Si occupa di cultura digitale, ecologia della rete e tecno-politica. Co-dirige la collana Culture Radicali per l'editore Meltemi e le collane Postuman3 e Selene per Mimesis edizioni. Collabora con il quotidiano Il Manifesto e con diverse testate on-line. Con il gruppo di ricerca Ippolita ha pubblicato Hacking del sé (2024), Etica hacker e anarco-capitalismo (2019), Tecnologie del dominio (2017), Anime elettriche (2016). Per cheFare, di cui è co-fondatore, ha curato il volume Cultura in trasformazione (2015).